STYLE AND INFLUENCES

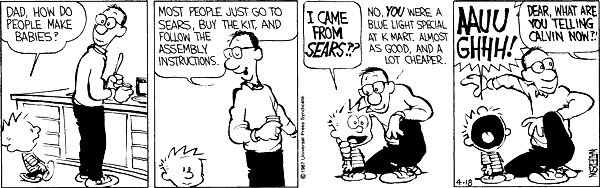

The strip borrows several elements and themes from three major influences: Walt Kelly's Pogo, George Herriman's Krazy Kat, and Charles M. Schulz's Peanuts. Schulz and Kelly particularly influenced Watterson's outlook on comics during his formative years.

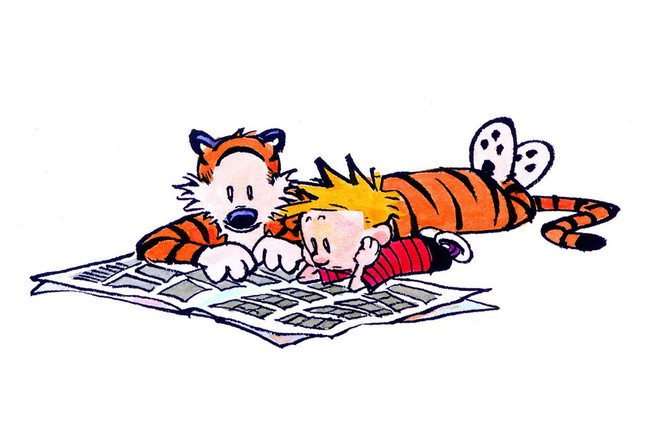

Notable elements of Watterson's artistic style are his characters' diverse and often exaggerated expressions (particularly those of Calvin), elaborate and bizarre backgrounds for Calvin's flights of imagination, expressions of motion, and frequent visual jokes and metaphors. In the later years of the strip, with more panel space available for his use, Watterson experimented more freely with different panel layouts, art styles, stories without dialogue, and greater use of whitespace. He also makes a point of not showing certain things explicitly: the "Noodle Incident" and the children's book Hamster Huey and the Gooey Kablooie are left to the reader's imagination, where Watterson was sure they would be "more outrageous" than he could portray.

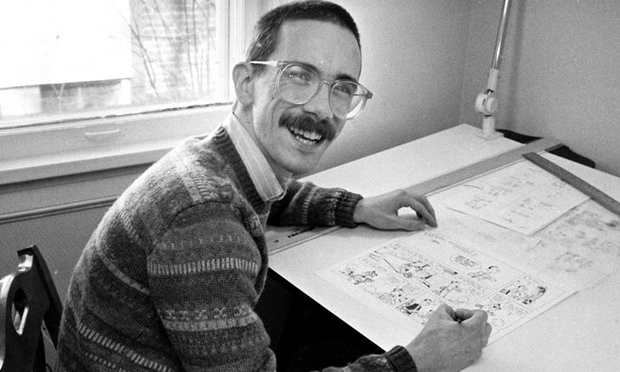

Watterson's technique started with minimalist pencil sketches drawn with a light pencil (though the larger Sunday strips often required more elaborate work) on a piece of Bristol board, with his brand of choice being Strathmore because he felt it held the drawings better on the page as opposed to the cheaper brands (Watterson said he would use any cheap pad of Bristol board his local supply store had, but switched to Strathmore after he found himself growing more and more displeased with the results). He would then use a small sable brush and India ink to fill in the rest of the drawing, saying that he did not want to simply trace over his penciling and thus make the inking more spontaneous. He lettered dialogue with a Rapidograph fountain pen, and he used a crowquill pen for odds and ends. Mistakes were covered with various forms of correction fluid, including the type used on typewriters. Watterson was careful in his use of color, often spending a great deal of time in choosing the right colors to employ for the weekly Sunday strip; his technique was to cut the color tabs the syndicate sent him into individual squares, lay out the colors, and then paint a watercolor approximation of the strip on tracing paper over the Bristol board and then mark the strip accordingly before sending it on. When Calvin and Hobbes began there were 64 colors available for the Sunday strips. For the later Sunday strips Watterson had 125 colors as well as the ability to fade the colors into each other.

Art and Academia

Watterson used the strip to poke fun at the art world, principally through Calvin's unconventional creations of snowmen but also through other expressions of childhood art. When Miss Wormwood complains that he is wasting class time drawing impossible things (a Stegosaurus in a rocket ship, for example), Calvin proclaims himself "on the cutting edge of the avant-garde." He begins exploring the medium of snow when a warm day melts his snowman. His next sculpture "speaks to the horror of our own mortality, inviting the viewer to contemplate the evanescence of life." In later strips, Calvin's creative instincts diversify to include sidewalk drawings (or, as he terms them, examples of "suburban postmodernism").

Watterson also lampooned the academic world. In one example, Calvin writes a "revisionist autobiography," recruiting Hobbes to take pictures of him engaged in such stereotypically childish activities as playing sports, in order to make him seem better adjusted to his society. In another strip, he carefully crafts an "artist's statement," claiming that such essays convey more messages than artworks themselves ever do (Hobbes blandly notes, "You misspelled Weltanschauung"). He indulges in what Watterson calls "pop psychobabble" to justify his destructive rampages and shift blame to his parents, citing "toxic codependency." In one instance, he pens a book report based on the theory that the purpose of academic writing is to "inflate weak ideas, obscure poor reasoning, and inhibit clarity," entitled The Dynamics of Interbeing and Monological Imperatives in Dick and Jane: A Study in Psychic Transrelational Gender Modes. Displaying his creation to Hobbes, he remarks, "Academia, here I come!" Watterson explains that he adapted this jargon (and similar examples from several other strips) from an actual book of art criticism.